HS:n jutussa ”Lisää valtaa? Ei kiitos, olemme Suomesta” (1.7.) sanottiin, ettei Suomen kansanedustajille kelpaa valta EU-asioissa. Kirjoituksen mukaan syy on siinä, että minun mielestäni ”hallituksen ja eduskunnan ei pidä ryhtyä EU-asioissa eri linjoille”, ja suuren valiokunnan jäsenet kunnioittavat tätä mielipidettä.

Kun Suomi vuonna 1995 liittyi Euroopan unioniin, haluttiin meillä turvata eduskunnan mahdollisimman laaja vaikutusvalta EU-asioiden käsittelyssä. Niinpä silloiseen perustuslakiin tehtiin tarkennuksia, jotka merkitsivät sitä, ettei hallitus saa EU:ssa päästää päätökseen ainuttakaan eduskunnan lainsäädäntö-, budjetti- tai sopimuksentekovaltaan kuuluvaa asiaa ilman eduskunnan suuren valiokunnan kautta ilmaisemaa kantaa.

Hallituksella on myös velvollisuus informoida eduskuntaa välittömästi saatuaan tiedon tällaisesta esityksestä sekä kaikista muistakin EU-asioista. Eduskunnalla on myös rajoittamaton tiedonsaantioikeus kaikista EU:iin liittyvistä asioista, eikä siltä voida esimerkiksi evätä asiakirjoihin tutustumista niiden salaisuuteen vetoamalla.

Suomalainen järjestelmä on toiminut hyvin. Siitä on otettu oppia ja mallia myös monissa muissa EU-maissa, jotka ovat samalla tavoin halunneet turvata parlamentaarisen demokratian toiminnan.

Se, että kaikissa maissa kansallisten parlamenttien asemaa ei kuitenkaan ole tyydyttävästi järjestetty, on merkittävin osa EU:n aiheellisesti arvostellusta demokratiavajeesta.

Joissain asemaltaan heikommissa parlamenteissa onkin ajoittain halua saada EU:n perussopimusten kautta parannusta asiaan. Suomi ja jäsenmaiden selvä enemmistö eivät ole tätä kannattaneet. Asia on tärkeä, mutta unioni ei voi eikä sen pidä yrittääkään säädellä jäsenvaltioittensa perustuslaillisia järjestelyjä.

Suomessa lähdetään siitä parlamentaarisen demokratian kulmakivestä, ettei meillä hallituksella voi EU-asioissakaan olla mitään erilaista kantaa kuin eduskunnalla, jonka luottamusta sen on nautittava.

Perustuslakisopimusneuvotteluissa tehdyt esitykset kansallisten parlamenttien aseman säätelystä EU-tasolla eivät siten tuo Suomen eduskunnalle yhtään lisää todellista valtaa.

Jos jokin komission esitys mielestämme loukkaisi läheisyysperiaatetta, niin Suomen eduskunta voi sen nytkin todeta ja edellyttää hallituksen myös vastustavan esitystä tällä perusteella.

Säädökset, jotka perustuvat siihen, että jäsenmaiden hallitukset ja parlamentit voisivat EU-asioissa edustaa toisistaan poikkeavia kantoja, ovat parlamentaariselle demokratialle vieraita ja jopa haitallisia.

EU:n toiminnan läpinäkyvyyttä, tehokkuutta ja ymmärrettävyyttä, joiden lisääminen oli yksi perussopimusuudistuksen lähtökohta, ei edesauta se, jos kansallisista parlamenteista pyritään tekemään vielä yksi uusi instituutio EU-päätöksenteon jo olemassa olevien instituutioiden lisäksi.

Suomen hallitukset ja eduskunta ovat koko EU-jäsenyytemme ajan olleet tätä mieltä kansallisten parlamenttien asemasta.

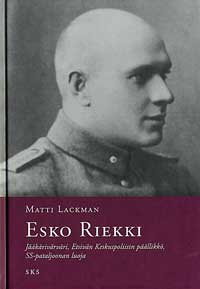

Juoniva aktivisti salaisena poliisina ja SS-värvärinä

Juoniva aktivisti salaisena poliisina ja SS-värvärinä